Photographed in his home in London, at the age of 104. Bill was both a prisoner and a medical officer who set up makeshift hospitals in the camps where ever possible. Soon after being captured and taken prisoner, Bill recognised the need for mental health support amongst the prisoners, attempting to provide support to those who needed it. However, it was only in his 90s that Bill began to speak about his experiences as a prisoner of war, even to his wife. I couldn’t reconcile the man I met with his age; on the day that I photographed him he was busy writing a paper for the British Journal of Medicine and had a number of meetings lined up for later that day.

Mess Tins acquired by Bob Hucklesby, from a fellow prisoner who had met his end in the jungle, unidentifiable but for the name etched onto the back. Bob claimed these mess tins saved his life countless times, for which he is forever grateful to Lt. Wootton. These tins could be used for many purposes, namely sterilising water over a fire. At the time of this photograph, Bob was still searching for the family of Lt. Wootton in order to pass on his gratitude for the tins that meant so much to him.

These jungles are almost entirely bamboo, where once large Teaks were numerous until chopped down, hauled by elephants under the direction of their mahouts, to be used for railway sleepers on the line. The fast growing and unstoppable bamboo has all but overgrown the sites that were once POW camps. It is a plant that seemed to have been a source of both survival and destruction, although proving useful to building almost any structure, its sharp stems were the cause of tropical ulcers. With the humid climate and putrid living conditions these often became sceptic, in many cases to the point of amputation. Here, bamboo surrounds the remains of the Pack of Cards Bridge build by the prisoners, so named for the several times it collapsed. Many claim it was sabotage by the prisoners themselves, in order to slow the transport of Japanese supplies.

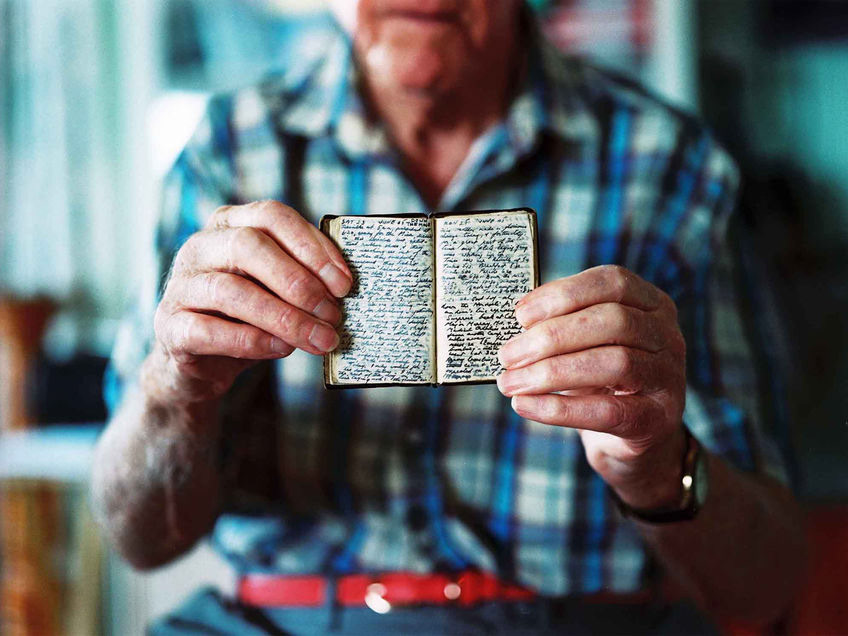

Photographed in his home in Ely at the age of 94, John Lowe shows me his prison diary. Fashioned himself from acquired materials, this miniature act of defiance would have cost him his life if found, but is now a valuable record. At the time of this photograph, John was Britain’s oldest ballet dancer, having taken it up at the age of 80 years old.

Travelling from Bangkok towards the famous "Bridge on the River Kwai". Leaving from Bangkok’s lesser known train station and stepping onto this old train, I felt immediately I was travelling into another realm with every mile towards Kanchanburi, the ticket collector a vision of the past and the rhythm of the train rattling around my head for hours after.

Former prisoner and survivor of the railway camps, photographed outside his home in Poole at the age of 97. After returning home from the Far East, Bob wanted nothing more than a simple life with his family in a comfortable home; he has lived in this house since his return and laid this paving himself. Speaking on survival, Bob recounted the memory of being sent to the makeshift hospital hut within the camp during a particularly vicious bout of illness. As cholera was rife, acute cases were isolated and Bob soon realised the severity of his situation. Determined to remain positive, he awoke the next morning from his delirium to find himself the only man of 20 that had survived the night. Surrounded by such devastation, this episode marked a distinct change in his attitude to survival; one of psychological endurance as much as physical.

Remnants of the railway and its route remain, continuously changing with the jungle's relentless growth. Hellfire Pass was notoriously deadly, claiming hundreds of lives under the harrowing labour conditions. The prisoners, forced to work throughout the night under the light of flame lamps, named the pass after the way in which their skeletal shadows danced against the rock in the flickering lamplight.

Lying on the banks of the Kwai Noi River, this cemetery remains on the site of the prison camp's original burial ground. The dead were buried away from the camp itself, or often burned, to prevent the spread of diseases such as cholera and laid to rest by their fellow prisoners. The space has been memorialised and is now run by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Local Thai staff tend to the cemetery and surrounding gardens with a meticulous dedication that I found incredibly touching.

Mrs Boonpong poses outside her brother's Chemist in Kanchanaburi city. A chemist by trade, he was also a member of the Thai resistance movement that worked to undermine the Japanese occupation. Mr Boonpong regularly provided medical supplies to resistance members that were able to get across the river and to the prison camps in order to supply the prisoners with crucial provisions, risking his life in the process. My own grandfather’s appendix was removed in the camps; surgical tools were either fashioned from found objects or acquired through such covert operations. Mrs Boonpong and her family preserve the original shop in the old part of the city. I came about them by chance on a hunt throughout the city for a new battery for my Bronica camera. My presence in the non-touristic part of the inner city attracted curiosity, after a few translations from passers by I found myself cycling behind a police woman’s car on her day off to introduce me to the Boonpong family.

Photographed at a Far Eastern Prisoners of War reunion, at Stratford Upon Avon, at the age of 94. Having joined the navy at 14 and subsequently lying about his age, he set off for the Far East still a boy. When his ship was sunk in the battle of the Java Sea, he survived the swim to shore, the water teeming with sharks attracted by the number of men in the water. He believes he was only left unscathed as the sharks must have 'had their fill' on those that swam before him. Having made it to shore, he was promptly taken prisoner.

This project is a visual journey to the place where my grandfather was held as a prisoner of war during WWII. He was one of 60 000 allied troops, along with 180 000 Asian civilian labourers, captured by the Japanese and forced to work on the building of a railway through Japanese occupied Thailand and into Burma.

The railway, intended to transport supplies between Japan’s occupied territories, was constructed almost entirely by hand using rudimentary tools and brute force. Known as ‘The Death Railway’, it claimed an estimated 90 000 lives as a result of disease, horrendous living conditions and brutal treatment by their captors that operated outside the bounds of the Geneva Convention. With the fall of Singapore in early 1942, many back home were led to believe that these captured soldiers saw out the rest of their war quietly combatting boredom within the relative safety of a prison camp. The reality was a daily fight for survival in extraordinary conditions battling starvation, torture and the jungle itself. At over 400km long, the number of deaths amounted in the construction of the railway infamously equate to a life claimed for every sleeper of the railway laid.

Most of these personal accounts only began to surface some 20 years after the events took place, with memories both preserved and muddied by trauma and the passing of time.

This work explores the landscape, the railway and former camp sites, informed by the collected accounts of the survivors that I interviewed and is an aesthetic response to the memories they shared with me. Intertwined with this is my own response to the various places I visited and the people that I encountered along the way. Although I never knew my grandfather, I am the only member of the family so far to have visited the railway, so this an intergenerational piecing together of his experience through various mediums and collective memory.

The railway, intended to transport supplies between Japan’s occupied territories, was constructed almost entirely by hand using rudimentary tools and brute force. Known as ‘The Death Railway’, it claimed an estimated 90 000 lives as a result of disease, horrendous living conditions and brutal treatment by their captors that operated outside the bounds of the Geneva Convention. With the fall of Singapore in early 1942, many back home were led to believe that these captured soldiers saw out the rest of their war quietly combatting boredom within the relative safety of a prison camp. The reality was a daily fight for survival in extraordinary conditions battling starvation, torture and the jungle itself. At over 400km long, the number of deaths amounted in the construction of the railway infamously equate to a life claimed for every sleeper of the railway laid.

Most of these personal accounts only began to surface some 20 years after the events took place, with memories both preserved and muddied by trauma and the passing of time.

This work explores the landscape, the railway and former camp sites, informed by the collected accounts of the survivors that I interviewed and is an aesthetic response to the memories they shared with me. Intertwined with this is my own response to the various places I visited and the people that I encountered along the way. Although I never knew my grandfather, I am the only member of the family so far to have visited the railway, so this an intergenerational piecing together of his experience through various mediums and collective memory.